Setup & Display blank a window

Lines before more or first 70 characters acts as page summary that will be shown

in the posts list in home page.

Vulkan is a very low-level spec that intends to keep as

little code overhead as possible.

gfx-hal is a library that closely resembles -

though not entirely - the Vulkan spec. It’s designed to

provide developers with a clean Vulkan-like API. Also,

gfx-hal provides multiple graphics backends to make our

code cross-platform compatible.

The following section is about Project Setup, which you can skip and directly go to

Vulkan Instance and Surfacesection to get a heads-up on Vulkan Instance and Surface.

Project Setup

Setting up a project in Rust is quite easy.

We just need to run:cargo new {{project_name}}

We need some essential modules as our project dependencies, used across every chapter.

Dependencies and Metadata

Cool, so let’s dive into Cargo.toml file for our dependencies

...

[features]

default = []

metal = ["gfx-backend-metal"]

dx12 = ["gfx-backend-dx12"]

vulkan = ["gfx-backend-vulkan"]

[dependencies]

winit = "0.22.0"

gfx-hal = "0.5.0"

log = "0.4.0"

log4rs = "0.11.0"

[dependencies.gfx-backend-vulkan]

version = "0.5.0"

features = ["x11"]

optional = true

[target.'cfg(target_os = "macos")'.dependencies.gfx-backend-metal]

version = "0.5.0"

optional = true

[target.'cfg(windows)'.dependencies.gfx-backend-dx12]

version = "0.5.0"

optional = true

[features]

We are focusing only on 3 leading platforms for now:

- Linux

- MacOS

- Windows

Thus, we require 3 different modules for each. gfx-backend-vulkan

for Linux/Windows, gfx-backend-metal for MacOS, gfx-backend-dx12

for Windows.

Details on how Rust Cargo features work can be read

in Link.

[dependencies]

Well, this section is quite clear:

winitis used for Cross-Platform Windowing Provider.gfx-halis used for Cross-Platform GPU Abstraction Layer Provider.logandlog4rscombined provide us with Logging Implementation in our project since we wouldn’t be usingprintln!macro.

[dependencies.{{feature}}] are the dependencies that will be installed conditionally depending on the user’s Operating System. We need to always run our project with one of the features enabled.

Code Setup

This tutorial maintains a single main.rs file with

just one struct that manages all the gfx-hal instances.

use std::mem::ManuallyDrop;

use std::ptr;

use gfx_hal::{window as hal_window, Backend, Instance};

use winit::{

dpi::{LogicalSize, PhysicalSize, Size},

event, event_loop, window,

};

#[cfg(feature = "dx12")]

use gfx_backend_dx12 as back;

#[cfg(feature = "metal")]

use gfx_backend_metal as back;

#[cfg(feature = "vulkan")]

use gfx_backend_vulkan as back;

use log::debug;

use log4rs;

const APP_NAME: &'static str = "Show Window";

const WINDOW_SIZE: [u32; 2] = [1280, 768];

struct Renderer<B: Backend> {}

impl<B: Backend> Renderer<B> {

fn new() -> Self {

Renderer {}

}

}

fn main() {

log4rs::init_file("log4rs.yml", Default::default()).unwrap();

}

The above code is our base structure, moving forward. We will do

very little work in fn main(), which includes making our

application up and running (also running the main Event Loop).

The heart of the whole application lies within struct Renderer

and all it’s implementations (Do note, in a real-world project,

you should properly plan and structure your application).

Lines 10-15: are conditional imports, depending on

which feature we would be running our application or build

it for release. If --features=metal is passed to cargo run,

it will run our application with gfx_backend_metal

backend.

gfx-backend-vulkan- Gets installed and used when

vulkanfeature is enabled - For Linux and Windows:

cargo run --features=vulkan

- Gets installed and used when

gfx-backend-metal- Gets installed and used when

metalfeature is enabled - For MacOS only:

cargo run --features=metal

- Gets installed and used when

gfx-backend-dx12- Gets installed and used when

dx12feature is enabled - For Windows only:

cargo run --features=dx12

- Gets installed and used when

Lines 17-18 & 32: are importing our log modules and

setting it up for logging. Once logging is setup, we can

call debug! macro anywhere in the code. To call other

Logging APIs, like info!, warn!, and more, we just need

to import them at Line-17.

gfx-hal Backend

Backends are specific to what GPU you have and what specs it supports.

Vulkan Backend is cross-compatible and has support in Linux/Windows, on AMD, Intel, NVidia.

Apple stays out, and I hate this thing about it. It doesn’t support Vulkan and has a specific graphics backend called

Metal. Thoughgfx-halhasmetalbackend as well and since I am using Mac (Yeah! Now don’t come and bash me, can’t use my Linux system a.t.m.), it would be a good way to know the support ofgfx-halfor MacOS as well.

Vulkan Instance and Surface

This tutorial is inspired from:

They are written in C++. I am trying to learn Rust and converting that tutorial into Rust,

using gfx-hal library, which is a wrapper over Vulkan Specs.

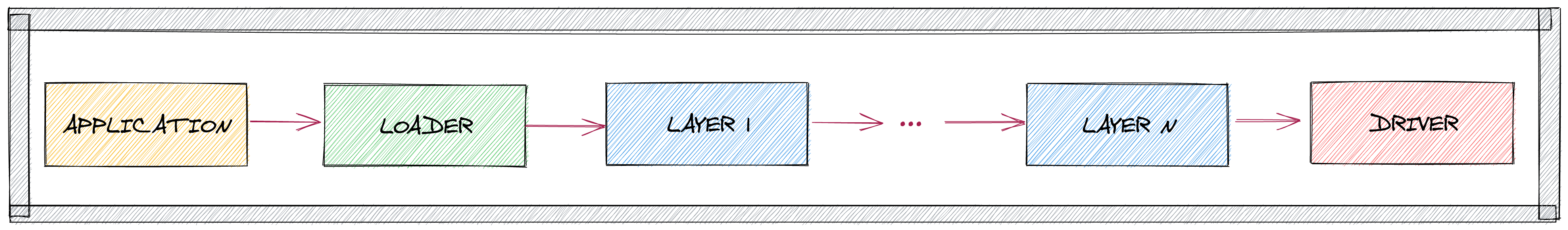

- Application: this whole project is the application.

- Loader: here refers to

gfx-halandgfx-backend-vulkanlibraries. An instance ofgfx-backend-vulkaninitializes a Loader. Creating an instance initializes the loader. - Layers: is something advanced, and I am not sure when or if I will talk about it at all.

Structure

The following structure is the minimal one, without Pipelines, Descriptors, Depth/Uniform Buffers, Shaders, and more (we will re-define our structure in coming chapters).

First few chapters, we will be rushing towards understanding the very basics and try to get our application running. Things really get boring if you don’t see any results, right!!!

Comments in the following code block are for reference, which you can skip and refer them later, once you start understanding the overall process better.

...

impl impl<B: Backend> Renderer<B> {

fn new() -> Self {

/**

* Do not worry about the following right now:

*

* Initialization Steps, like:

* * Get gfx-hal adapter

* * Get Devices and Device Queues and Supported Family

* * Setup Swapchain

* * Initialize Render Pass

* * Create Command Pool and get Command Buffers from them

* * Initialize Synchronization Primitives

*/

Renderer {}

}

fn draw() {

/**

* Draw calls are required to update our Window Frames, respective to OS's refresh rate.

*

* Thus we need the following:

* * Update our Current Frame Index, to keep a check on which frame we are.

* * Get an Image that we will draw to our screen

* * Create a Framebuffer that links the Image resource to Render Pass

* * Lock process

* * Begin recording commands

* * End recording commands

* * Submit Commands to Device Queue.

* * Presenting to screen

* * Unlock processes

*

* (Semaphore and Fence) Locking/Unlocking processes run in parallel, so above sequence

* will differ when implemented.

*/

}

}

impl<B: Backend> Drop for Renderer<B> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

// Clean-Up Code, for some resources that are manually managed...

}

}

...

fn main() -> Result<(), &'static str> {

/**

* Various instantiation steps are required before creating

* our Render:

*

* * Instantiate Window Event Loop

* * Instantiate OS Window Instance and get Window Dimension Extents

* * Instantiate Vulkan(gfx-hal backend) Instance and Surface

* * Instantiate our Renderer {}

* * Start our Window Event Loop:

* * -> Renderer Draws to Screen every Window redraw

* * Application gets Killed, Event Loop drops.

*/

}

Creating OS Window

Now let’s come back to our code. In the real-world, to draw

anything, we need a canvas, right. Similarly, in

Computer Graphics to draw anything, we need an OS Window.

Later we will be binding this OS Window with GPU surface

instance that will do the actual drawing. Creating an OS Window

in Rust is done using winit library, which again is

cross-platform. It requires two significant steps to

display a blank window:

- Window Dimensions

- Event Loop will help us know when to redraw, w.r.t CPU and GPU capabilities (since we are working with Vulkan, it’s all GPU capabilities), and listen to user events.

How or When re-renders happen, is all very low-level details, which I don’t have much context on right now.

...

// main function will start instantiation of static instances.

fn main() {

...

let ev_loop = event_loop::EventLoop::new();

let (window_builder, extent) = build_window(&ev_loop);

let (window) = create_backend(window_builder, &ev_loop, extent);

...

}

build_window() is doing the main job of instantiating

the main OS window, with some logical window size, scaled to

match the actual physical size.

...

fn create_backend(

wb: window::WindowBuilder,

ev_loop: &event_loop::EventLoop<()>,

extent: hal_window::Extent2D,

) -> (back::Instance, back::Surface, window::Window) {

let window = wb.build(ev_loop).unwrap();

(window)

}

fn build_window(

ev_loop: &event_loop::EventLoop<()>

) -> (window::WindowBuilder, hal_window::Extent2D) {

let (logical_window_size, physical_window_size) = {

let dpi = ev_loop.primary_monitor().scale_factor();

let logical: LogicalSize<u32> = WINDOW_SIZE.into();

let physical: PhysicalSize<u32> = logical.to_physical(dpi);

(logical, physical)

};

let window_builder = window::WindowBuilder::new()

.with_title(APP_NAME)

.with_inner_size(logical_window_size);

(

window_builder,

hal_window::Extent2D {

width: physical_window_size.width,

height: physical_window_size.height,

},

)

}

Everything in the above code is quite self-explanatory and

straightforward. The only thing that seems confusing is, why

do we have two device sizes. The best explanation can be found

here in winit docs,

but in short, they are just two different size

instances. One (the LogicalSize) is Human understandable,

i.e., what you ask for is what you get. The other one

(PhysicalDevice) is something specific to OS and hardware,

where each Computer System might have a different Screen

display ratio (also known as DPI or PPI), defining how a 720 sized

Logical window we defined will be presented on real

Screen, calculating the pixel ratio per inch and stuff.

window instance, which

is nothing but winit’s Window instance, is built by the

WindowBuilder we instantiated earlier. This window will

be used by surface to bind them together.

We will discuss the Event Loop in a later section.

Vulkan Instance & Surface instance creation

We now have to create instances of Vulkan Backend Instance

and Surface. These two states will only be used for instantiating

and destroying other useful resources; thus, we will have to

keep them in Renderer struct.

We will update our create_backend function, which will

give us (instance, surface) instances for later use.

The above code will give us instances of Vulkan Instance and Surface,

but we need them in Renderer struct as well for later reference.

Thus we need to update our Renderer struct as well.

Details on the above code:

We will discuss

extentin another chapter in detail, but in short, it` will help us keep window dimension details.

instance is created directly from static functions from

gfx_hal Instance. create function takes an APP_NAME

and a VERSION number for the app, whose functionality is

currently unknown to me.

instance is used to create surface. Vulkan requires a

canvas or surface to draw things into, and a surface can

only exist inside an OS App Window. Usually, we use a 3rd-party

module to create OS specific Window instances,

like we created one from winit.

One thing to note: gfx-hal does not manage every piece of Memory,

up here, like surface was created using instance. Thus we

need to manage such resources, which need to be cleared

from memory before other resources, such as instance.

Therefore, we define such instances like

Vulkan surface, as manually managed using ManuallyDrop

struct, and we need to drop surface once done with it,

i.e., before Renderer struct gets dropped.

ManuallyDrop is a module that gives any developer a

secure way to clear the memory in Rust. Instead of ManuallyDrop::drop

we are using ManuallyDrop::into_inner, because we need to

get the actual data from memory and pass it’s ownership to

Vulkan instance for destruction.

Bonus Round (Event Loop)

Ok! We have already created ev_loop instance for winit,

but we haven’t discussed it properly. As the

name suggests, it is the core of winit, used for starting the

App and listening to User Events.

We will discuss Event Handling done inside the run loop,

where we pass a Closure, which will handle various user events,

like Keyboard, Joystick, Mouse events.

Do remember that a Closure will completely get the ownership of any variables that are passed to it.

Even theev_loopinstance we created, will lose its ownership afterev_loop.runcall. That’s why everything we have done until now is done insidemainfunction to keep instance ownerships temporary.

fn main() {

// Previous instantiations, before starting the

// event_loop

...

ev_loop.run(move |event, _, control_flow| {

*control_flow = event_loop::ControlFlow::Wait;

match event {

event::Event::WindowEvent { event, .. } =>

{

#[allow(unused_variables)]

match event {

event::WindowEvent::CloseRequested => {

*control_flow = event_loop::ControlFlow::Exit

}

event::WindowEvent::Resized(dims) => {

debug!("RESIZE EVENT");

}

event::WindowEvent::ScaleFactorChanged { new_inner_size, .. } => {

// Will get called whenever the screen scale factor (DPI) changes,

// like when the user move the Window from one less DPI monitor

// to other high scaled DPI Monitor.

debug!("Scale Factor Change");

}

_ => (),

}

}

event::Event::MainEventsCleared => {

debug!("MainEventsCleared");

backend.window.request_redraw();

},

event::Event::RedrawRequested(_) => {

debug!("RedrawRequested");

},

event::Event::RedrawEventsCleared => {

debug!("RedrawEventsCleared");

}

_ => (),

}

});

...

}

First things first, ev_loop.run(|| => {}) starts our event

loop, which actually takes a closure.

Thus we need to be a bit careful in using it. That’s one of the reasons

we instantiated everything inside main. Later on, we will

do things inside struct impls, but in this section, we have

sone most of the work inside main.

Details on event listeners:

CloseRequestedis used for listening close button click. Without this, our Window won’t Shutdown gracefully, we would have toSIGKILLour app. We can also listen to Key presses, likeESC, to close the window, but we will cover that later.ResizedandScaleFactorChangedare called when window is resized and when window’s DPI changes (like when we move our window from a low DPI Monitor to High DPI), respectively.MainEventsCleared: If you are from Android background, it resembles theonMeasurecall, or if from ReactJS world, it resembles theshouldComponentUpdatecall. What I mean is, this event is called just before any redraw and can be used to do calculations before drawing on window. Also, keep a note that if you want to redraw you need to call thiswindow.request_redraw(), like wereturn truefromshouldComponentUpdateto do arender.RedrawRequested: this resembles Android’sonDrawcall and in ReactJS resembles arendercall. That means this call is where we will have to handle all our canvas drawings, ingfx_hal, all oursurfacedrawings.RedrawEventsCleared: this resembles ReactJScomponentDidUpdatecall, as this event gets triggered on each change after a redraw has happened. One thing to note, if there are noRedrawRequestedevents, it is emitted immediately afterMainEventsCleared.

2020-05-11T06:59:42.987942+05:30 DEBUG show_window - MainEventsCleared

2020-05-11T06:59:42.988007+05:30 DEBUG show_window - RedrawRequested

2020-05-11T06:59:42.988033+05:30 DEBUG show_window - RedrawEventsCleared

Code & Output

You can find the full code for this Doc, here 001-show_window

Once you run the code (cargo run --bin show_window --features=vulkan),

you will get the following output.